Americans see value in higher education, survey finds, but are unhappy with current systemThe results of this survey are likely to be seized on by various constituents and interests. No doubt state legislators will see it as further evidence of the need for "reform" in higher education.

I don't intend to argue here about whether universities need to reform or not. In a certain sense, that's a silly question - all universities at all times can do things to make themselves better, and should. We can all find ways to better serve our students, to help our students learn and grow more, to be more efficient and cost-effective, and so on. This is the normal state of affairs.

One thing state legislatures and the general public don't often realize is that, despite our desire for simple answers, the kinds of change needed are usually university-specific. Even within one state or public university system, the issues and challenges facing any two universities within that area are likely to be very different. I have recently made the transition from one public university in Ohio to another. Both are sizable comprehensive universities serving metropolitan areas that in many ways are mirror images of each other. Both need reform. The kind of reform each needs, however, is radically different.

So a survey that says "things need to change!" isn't useful at all. Very few doubt the need for change on any campus, and those who do tend not to be in positions of authority or influence. Yes, there are rear-guard actions by groups of faculty or (less frequently) staff, but these are increasingly ineffective. Most good faculty leaders I know understand the need for reform. We just need to agree on what kinds of reforms are needed.

But the survey referenced above isn't just useless because it makes an obvious point. The observation that "58% believe colleges put their own interests ahead of students", or that "just one in four respondents feel higher education is functioning fine the way it is", reflect genuine opinions. But where do those opinions come from? As has famously been said, everyone is entitled to their own opinions but not their own facts.

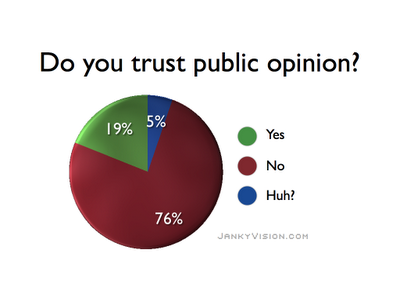

Legislators or others with an agenda will argue that these opinions are evidence that things have gone wrong in higher education, that there is a "crisis". They assume, in other words, that people's opinions reflect reality. Unfortunately, that's not true.

If you call me up and ask me what I think of the nature of the health care system in the US, I have to construct an opinion on the spot. Like most Americans, I don't spend a lot of time thinking about "the health care system". I occasionally interact with that system, because (like most Americans) I tend to be generally healthy. Moreover, even if I like my particular doctor, I may not see that one data point as representative of the system as a whole. I'm likely to simply think that my doctor is a good fellow, or that my doctor's office is a nice and reasonably well-run place.

So where does my opinion come from? If I read stories all the time about how health care is "failing", how people can't get treatment, how drugs are too expensive, how hospitals are terrible, and so on - those things are likely to be "top of mind" for me when the pollster calls. We have known for a long time that in public opinion polling, people base their answers on the most recent relevant information in their memory banks, even if that information isn't that representative or even all that relevant.

So when somebody does a poll of 1600 people nationwide and asks their opinions about college, I know that the vast majority of those respondents are unlikely to have had a significant interaction recently with a college. Moreover, even if they have, we tend to differentiate the individual cases we know from the broader "system" we're being asked about. This is the same dynamic that leads most Americans to despite Congress, yet like their own individual representative. So the "raw material" we're likely to base our opinion on when asked about "the higher education system" is the general stream of stories and headlines we're exposed to in media coverage and our social media streams.

Polls like this, in other words, are self-fulfilling prophecies for politicians who have been railing against higher education for years. They don't reflect the reality of higher ed; they don't even reflect the reality of individuals' experience with higher ed. They reflect the narrative we have constructed of a "system in crisis" - a narrative that has been built to serve specific interests, mostly in service to political ambition.

The media (including the higher ed press and the social media sphere - bloggers included!) play into this. A handful of stories about interrupted speeches on college campuses created a narrative that we have a "crisis" of free speech on campus. Stories of free speech rights being appropriately exercised and protected don't make the news or the blogs, although I have personally seen more of that than of the "bad" cases. In my own small way, I'm guilty of perpetuating the problem here.

None of this is news. We know this is the way public opinion works, and have at least since John Zaller published The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion back in 1992. But polls make good headlines, which then further feed narratives.

For those of us in higher education: we need to stop playing defense and responding to specific charges, and build a different narrative. We have the tools and we have the facts. The reality is that American higher education is the envy of the world, which is why the United States brings in far more students from overseas than any other country. We need to tell that story, and enlist allies to help us tell it broadly and publicly.

For the broader public: we need to develop the skills that everyone keeps saying we need - critical thinking. The level of education needed to develop a little critical distance and not swallow a particular story wholesale is not unattainable. It probably doesn't even require a bachelor's degree. What it does require is training and practice (which higher education are designed to provide), and a willingness to think a little. That latter point is up to the rest of us.

No comments:

Post a Comment